For many years, the University of Tennessee Libraries has utilized GeoNames as a source

for dereferencing and reconciling geographic location data related to our works. The GeoNames API allows consumers to retrieve

many metadata elements about a place for free including "point" information in the form of latitude and longitude. The

relative ease of adding geographic data has encouraged us to add this data to our MODS records at

/mods/subject[geographic]/cartographics/coordinates near its corresponding string and reference to the source

object in Geonames.

1 2 3 4 5 6 | <mods:subject authority="geonames" valueURI="http://sws.geonames.org/4624443"> <mods:geographic>Gatlinburg</mods:geographic> <mods:cartographics> <mods:coordinates>35.71453, -83.51189</mods:coordinates> </mods:cartographics> </mods:subject> |

While we historically mapped this data, we never actually leveraged it and used it for display or navigation.

Recently, the Center for Digital Humanities at Saint Louis University

released a new Beta viewer that leverages

navPlace properties in IIIF manifests and displays them on a map. Depending on where the data is found within the

manifest depends on how it functions in the viewer. Since we already had this data easily available, I decided to add

code to add navPlace properties to our manifests via our IIIF Presentation v3 service.

The IIIF Presentation Specification does not provide a resource property

designed specifically for geographic location. Because of this, the navPlace extension

exists. The navPlace extension is not very prescriptive. The

property is allowed in most classes defined by the IIIF presentation v3 specification.

According to the extension, a navPlace property is allowed on a IIIF Collection, Manifest,

Range, and / or Canvas.

Rather than adding the property everywhere, I decided to start small by adding the properties only to Manifests

and Ranges. While one may argue that it makes most sense to add this information to the Collection, I

would argue that the behavior of navPlace viewer

makes this unnecessary. That's because the viewer attempts to dereference all id properties in search of other

navPlace properties that may appear in embedded classes. Because of this, a Collection that references a

Manifest with an navPlace property will render those if the Collection is passed to the viewer.

In the next few sections, I will describe our implementation, how the viewer consumes and makes use of them, and personal desires for future consuming applications.

Content State and Desires for Consuming Applications

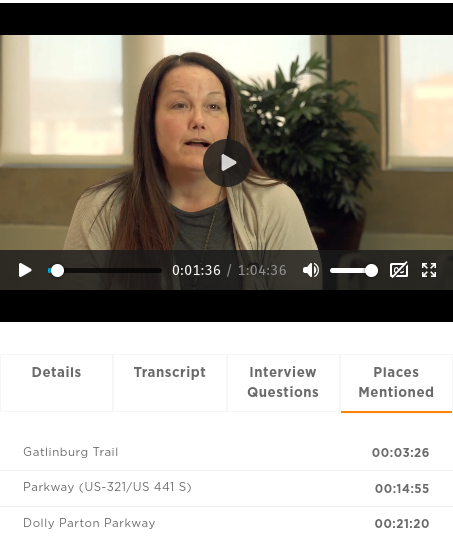

While the delivery of navPlace data on manifests in navPlace viewer meets our needs, the delivery of the property

on range leaves a lot to be desired. The temporal data associated with the canvas inside the range is used to provide

navigation to specific points in an audio or video work in viewers such as Universal Viewer and our own RFTA canopy. For

instance, in our Rising from the Ashes oral history portal, the range data is leveraged to

provide users a way to navigate to specific interview questions or geographic locations discussed within an oral history

work. When a user clicks a temporal based part, it causes the viewer to update to that specific point.

In my opinion, this navigation experience would be better if it were a map with navigable points rather than the list you see above. Furthermore, this could be enhanced even further by allowing the map to represent an entire collection of manifests and rendering the navPlace properties on each. Then, users could start at the map and navigate to specific points in works without starting at the work.

In order for this to happen, this will require two things. First, the map viewer or initial consuming application must

translate the range to a IIIF content state URI. Content state provides a

way to refer to a IIIF Presentation API resource, or a part of a resource, in a compact format that can be used to

initialize the view of that resource in any client. The id associated with the range is not intended to be passed

to a viewer in the same form that its found in the manifest. Instead, it must be transformed into a content state URI. To

do this, the viewer needs to take the range and convert it to an annotation body like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | { "@context": "http://iiif.io/api/presentation/3/context.json", "id": "https://digital.lib.utk.edu/assemble/content-states/1", "type": "Annotation", "motivation": ["contentState"], "target": { "id": "https://digital.lib.utk.edu/notderferenceable/assemble/manifest/rfta/8/range/places_mentioned/1", "type": "Range", "partOf": [ { "id": "https://digital.lib.utk.edu/assemble/manifest/rfta/8", "type": "Manifest" } ] } } |

Then, this JSON needs to be encoded according to the IIIF Content State Specification to ensure it is not vulnerable to corruption. The specification defines a two step process for doing this that uses both the encodeURIComponent function available in web browsers, followed by Base 64 Encoding with URL and Filename Safe Alphabet (“base64url”) encoding, with padding characters removed. The initial encodeURIComponent step allows any UTF-16 string in JavaScript to then be safely encoded to base64url in a web browser. The final step of removing padding removes the “=” character which might be subject to further percent-encoding as part of a URL.

With Python, the JSON body above can be encoded into a content state URL like so:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | import base64 from urllib import parse import json def encode_content_state(plain_content_state): uri_encoded = parse.quote(plain_content_state, safe='') # equivalent of encodeURIComponent utf8_encoded = uri_encoded.encode("UTF-8") base64url = base64.urlsafe_b64encode(utf8_encoded) utf8_decoded = base64url.decode("UTF-8") base64url_no_padding = utf8_decoded.replace("=", "") return base64url_no_padding if __name__ == "__main__": my_file = open('sample_range.json') x = json.load(my_file) encode_content_state(json.dumps(x)) |

This will return an encoded string that can decoded by a viewer that supports the specification. An anchor can be built that passes this string following content state convention:

1 2 3 | <a href="https://link_to_viewer?iiif_content=JTdCJTIyJTQwY29udGV4dCUyMiUzQSUyMCUyMmh0dHAlM0ElMkYlMkZpaWlmLmlvJTJGYXBpJTJGcHJlc2VudGF0aW9uJTJGMyUyRmNvbnRleHQuanNvbiUyMiUyQyUyMCUyMmlkJTIyJTNBJTIwJTIyaHR0cHMlM0ElMkYlMkZkaWdpdGFsLmxpYi51dGsuZWR1JTJGYXNzZW1ibGUlMkZjb250ZW50LXN0YXRlcyUyRjElMjIlMkMlMjAlMjJ0eXBlJTIyJTNBJTIwJTIyQW5ub3RhdGlvbiUyMiUyQyUyMCUyMm1vdGl2YXRpb24lMjIlM0ElMjAlNUIlMjJjb250ZW50U3RhdGUlMjIlNUQlMkMlMjAlMjJ0YXJnZXQlMjIlM0ElMjAlN0IlMjJpZCUyMiUzQSUyMCUyMmh0dHBzJTNBJTJGJTJGZGlnaXRhbC5saWIudXRrLmVkdSUyRm5vdGRlcmZlcmVuY2VhYmxlJTJGYXNzZW1ibGUlMkZtYW5pZmVzdCUyRnJmdGElMkY4JTJGcmFuZ2UlMkZwbGFjZXNfbWVudGlvbmVkJTJGMSUyMiUyQyUyMCUyMnR5cGUlMjIlM0ElMjAlMjJSYW5nZSUyMiUyQyUyMCUyMnBhcnRPZiUyMiUzQSUyMCU1QiU3QiUyMmlkJTIyJTNBJTIwJTIyaHR0cHMlM0ElMkYlMkZkaWdpdGFsLmxpYi51dGsuZWR1JTJGYXNzZW1ibGUlMkZtYW5pZmVzdCUyRnJmdGElMkY4JTIyJTJDJTIwJTIydHlwZSUyMiUzQSUyMCUyMk1hbmlmZXN0JTIyJTdEJTVEJTdEJTdE"> Link to Viewer </a> |

Then, the consuming application can decode this URI according to the specification like so:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | import base64 from urllib import parse import json def decode_content_state(encoded_content_state): padded_content_state = restore_padding(encoded_content_state) base64url_decoded = base64.urlsafe_b64decode(padded_content_state) utf8_decoded = base64url_decoded.decode("UTF-8") uri_decoded = parse.unquote(utf8_decoded) return uri_decoded if __name__ == "__main__": content_state = "JTdCJTIyJTQwY29udGV4dCUyMiUzQSUyMCUyMmh0dHAlM0ElMkYlMkZpaWlmLmlvJTJGYXBpJTJGcHJlc2VudGF0aW9uJTJGMyUyRmNvbnRleHQuanNvbiUyMiUyQyUyMCUyMmlkJTIyJTNBJTIwJTIyaHR0cHMlM0ElMkYlMkZkaWdpdGFsLmxpYi51dGsuZWR1JTJGYXNzZW1ibGUlMkZjb250ZW50LXN0YXRlcyUyRjElMjIlMkMlMjAlMjJ0eXBlJTIyJTNBJTIwJTIyQW5ub3RhdGlvbiUyMiUyQyUyMCUyMm1vdGl2YXRpb24lMjIlM0ElMjAlNUIlMjJjb250ZW50U3RhdGUlMjIlNUQlMkMlMjAlMjJ0YXJnZXQlMjIlM0ElMjAlN0IlMjJpZCUyMiUzQSUyMCUyMmh0dHBzJTNBJTJGJTJGZGlnaXRhbC5saWIudXRrLmVkdSUyRm5vdGRlcmZlcmVuY2VhYmxlJTJGYXNzZW1ibGUlMkZtYW5pZmVzdCUyRnJmdGElMkY4JTJGcmFuZ2UlMkZwbGFjZXNfbWVudGlvbmVkJTJGMSUyMiUyQyUyMCUyMnR5cGUlMjIlM0ElMjAlMjJSYW5nZSUyMiUyQyUyMCUyMnBhcnRPZiUyMiUzQSUyMCU1QiU3QiUyMmlkJTIyJTNBJTIwJTIyaHR0cHMlM0ElMkYlMkZkaWdpdGFsLmxpYi51dGsuZWR1JTJGYXNzZW1ibGUlMkZtYW5pZmVzdCUyRnJmdGElMkY4JTIyJTJDJTIwJTIydHlwZSUyMiUzQSUyMCUyMk1hbmlmZXN0JTIyJTdEJTVEJTdEJTdE" decode_content_state(content_state) |

Assuming the viewer supports content state, the video can then start at the same temporal media fragment as in the Beck Jackson example above.

While this may all seem like a big ask, I personally want to IIIF and its various APIs to power our future repositories. In order to make this happen, consuming applications must be able to recognize, encode, and decode content state. While we aren't there yet, I am hopeful we will see this support in the future.